Tags

Congress, Devaluation, Economic Crisis, Forex, IMF, Parliament, Politics, Reforms, Socialism, The Syndicate

It appeared a perfectly normal weekend day on Sunday, 5th June 1966. The Delhi summer was at its height and in all probability, the person who felt it more than most was Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. A momentous decision was to be announced the following day and she was doubtless aware of the fact that it was bound to have serious repercussions. Nonetheless, there was no option but to go ahead.

Unknown to her, Mrs. Gandhi was to unleash forces which would have a long lasting effect on her own self, her party as well as her country.

An Economic Crisis

1965-66 was, without doubt, India’s annus horribilis. The agricultural crisis of the 60s had reached a flashpoint with a devastating drought in 1965, soon followed by an unexpected war against Pakistan which further strained an already desperate economic situation. While the population had grown rapidly from 439 Million in 1961 to around 500 Million by 1966, the economy had sputtered along at 3.2%. Not surprisingly, inflation had reached a whopping 11% by 1965.

Indira Gandhi

Elsewhere, a balance of payments crisis had been steadily building up. Between 1950-51 and 1965-66, India’s exports had grown 20% even as imports had shot up by 131%. By 1965, India’s trade deficit had reached a perilous 930 crores at a time when foreign exchange reserves were limited. To support India in its hour of need, the World Bank’s Aid to India Consortium (AIC) had committed $1 Billion in aid for 1962 and 1963, followed by $3 Billion each year from 1964 to 1966.

By 1965, the situation had become so dire that the AIC had appointed a commission under American economist Bernard Bell to make its recommendations for salvaging the situation. The report recommended, among other things, devaluation of the Indian currency.

Power of the Currency

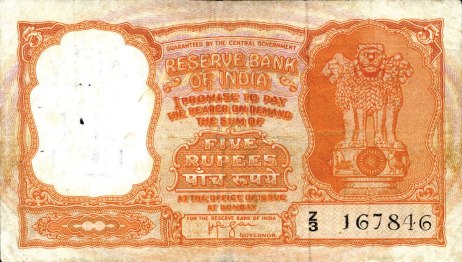

The Indian Rupee in that era was still pegged to the Pound Sterling at a fixed rate of Rs. 13.33/ Pound. It was, as a matter of fact, the currency used in the entire Gulf region. From 1959 onwards, the Government of India had introduced the Gulf Rupee, for exclusive circulation outside India. From Beirut in West Asia to Hong Kong in the far east, the Indian Rupee was officially or unofficially a commonly accepted tender.

All of that was soon set to change.

Who Will Bell the Cat?

Economists across the world (including many in India) were widely of the opinion that the Indian Rupee was grossly overvalued, which meant that buyers of goods exported from India had to pay more than the goods were actually worth, while imports were cheap. The over-valuation made Indian exports non-competitive in the international market, while at the same time encouraging imports.

With a balance of payments crisis, the most logical solution was to devalue the currency. Unfortunately, the value of the currency was ignorantly equated with national pride (as it still is to some extent). A decision to devalue it, while economically sound, could prove politically disastrous.

Such political considerations meant little to the World Bank, which suspended all financial assistance in 1965, until the Indian currency was devalued to reflect its true worth. Prime Minister Shastri, a pragmatic man if ever there was one, decided to take the plunge towards the end of the year. To this end, he ‘eased out’ his intransigent Finance Minister T.T. Krishnamachari and replaced him with the pliable Sachindra Chaudhari. The stage was set for far reaching economic reforms.

Unfortunately, there came an unexpected development at this stage. Shastri’s untimely death in January 1966 saw the relatively inexperienced Indira Gandhi come to power. Confronted by the economic crisis, Mrs. Gandhi made a trip to Washington in April to try and find a way out. After a chastening visit to the USA and consultations with economists and policymakers in the country, she finally bowed to the inevitable.

Indira Bells the Cat

On Monday, 6th June, Indira Gandhi announced the decision to devalue the Indian Rupee to her bemused cabinet of ministers. So fearful had she been of political repercussions, that discussions on the subject had been held in strict secrecy, so much so that her ministers were taken completely off guard. Despite the element of surprise (or possibly because of it) the cabinet accepted the ultimatum with the sole exception of Manubhai Shah, then Minister for Foreign Trade.

And so at 9:30 P.M on 6th June 1966, Finance Minister Sachindra Chaudhari announced the decision to devalue the Indian Rupee by a staggering 36.5%. By virtue of the conversion rate between the Pound Sterling and the US Dollar, the value of the Indian currency plummeted from Rs. 4.76/$ to Rs. 7.50/$ overnight.

To Do or Not to Do?

The Syndicate, which was the real power behind the throne, was blissfully unaware of the developments in New Delhi. And so at this late hour, Indira Gandhi got in touch with the powerful party president K Kamaraj. Whether the non-communication was a deliberate ploy to forestall any opposition, or simply an oversight on Mrs. Gandhi’s part is anybody’s guess.

Kamaraj’s reaction proved far worse than anything the Prime Minister could have possibly foreseen. Shaken up by his hostile response, she contemplated postponing the decision. Unfortunately, she soon discovered that the matter was out of her hands, as the International Monetary Fund had already been notified by Chief Economic Adviser I.G. Patel. For the better or the worse, the die was cast.

A Storm of Protest

The Syndicate was hardly alone in its opposition to the decision. In parliament, opposition members across party lines vociferously condemned the devaluation of the Rupee. In an era when most Indians had distinct memories of the colonial era, distrust of the ‘imperialist’ west was but natural. To members of parliament (MPs), the devaluation was seen as the ultimate sellout to America. Beneath the surface, many members on the treasury benches empathised with the opposition. Kamaraj is believed to have described the situation as

…a great man’s daughter, a small man’s mistake…

Kamaraj was referring to his own mistake in making her the Prime Minister, a point on which many Congress MPs concurred with him. Nonetheless, he discouraged those who wanted Indira Gandhi to be removed. The party would have to contest elections in a few months time and without the colossal presence of Nehru, it could ill-afford a divided house.

And so Indira Gandhi lived to fight another day.

Aftermath

- The Syndicate turned hostile to Indira Gandhi, who would be repeatedly embarassed by her own party MPs on the floor of the parliament in the coming months

- The Congress narrowly held on to power, winning a narrow majority in the 1967 elections

- The Indian Rupee became a global pariah following the devaluation. Gulf states adopted their own currencies in the years that followed

- The World Bank, citing the inadequacy of economic reforms, refused to deliver on its promise of economic assistance

- Yet another drought in 1966 would lead to further economic hardships, including runaway inflation, much of which would be (wrongly) blamed on the devaluation

- The combination of currency devaluation and import substitution brought down the trade deficit from Rs. 930 crores in 1965 to 100 crores in 1970

- I.G. Patel turned down the offer to be appointed as Finance Minister twenty-five years later (when the Indian economy, coincidentally, faced a similar crisis), paving the way for Dr. Manmohan Singh to champion the economic reforms of 1991.

Legacy

- The bitter opposition from Kamaraj & co prompted Indira Gandhi to destroy the Syndicate and seize complete control over the party

- Mrs. Gandhi split the party in 1969. Her faction, which would be recognised by the election commission as legitimate successor to the old Congress party, enjoyed power at the centre for all but twelve years in the period between 1971 and 2014.

- Feeling betrayed by the western powers and having lost much credibility as well as political capital, Indira Gandhi increasingly turned to socialist policies to preserve her position, further shackling the Indian economy in the decades that followed

- The lack of appetite for follow-up reforms left the Indian economy with structural shortcomings, setting the stage for the economic crisis of 1991

- The uproar following the devaluation of the currency would impel the Narasimha Rao Government in 1991 to undertake similar measures in a measured and clandestine manner

Sources

- Inder Malhotra, A Storm of Protest, Indian Express, 27th May 2013

- Sujay Gupta, Indira Gandhi’s Rupee Devaluation Master Stroke, Economic Times 7th June 2016

- Why 6/6/’66 was a devilish day for the Indian Rupee, http://www.Livemint.com, 6th June 2016

- T.N. Ninan, Story of Two Devaluations, Business Standard, 16th August 2013

- R. Nagaraj, Growth Rate of India’s GDP, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol.25 No. 26 (30th June 1990)

- Ankit Mittal, India and Liberalisation: There was a 1966 before 1991, Livemint.com, 24th January 2016

- Official website of Envis Centre on Population and Environment