As we saw in the previous article, a dispute over succession to the throne of the Nizam of Hyderabad led to a fresh round of hostilities between the British and French companies. The French supported Chanda Sahib, claimant to the throne of the nawab and the British sided with Mohammed Ali, son of the late nawab.

Chanda Sahib and his French allies held the upper hand as they laid seige to the British garrison at Tiruchirapalli. Confronted by a vastly superior opponent, it was proposed to stage a diversionary attack on Arcot, the capital of the nawab of Carnatic, under the leadership of Robert Clive, a 25 year old writer with the East India Company who had just taken up a military posting.

The Siege of Arcot

The plan was communicated to the company governor at Madras, Saunders, who immediately gave his approval and instructed Clive to return to Madras and take charge of the army that would attack Arcot. On 26th August 1751, Robert Clive set off from Madras at the head of 200 European and 500 Indian sepoys. Despite the sheer exhaustion of the trying journey, the troops found Arcot so poorly defended, that the fort was besieged and the town surrendered without a single casualty. The surprise had been complete.

Robert Clive

But it was a case of winning only the battle. The war was far from over. Clive had less than a thousand troops to hold the town and a (numerically) far superior enemy army was camped in the vicinity. The situation was further compounded by the fact that some of the soldiers had to be sent back to Madras, since Governor Saunders had transferred some of his own troops to Clive and consequently, was left in a very precarious position. Those troops gone, Clive had only 120 British and 200 Indian sepoys at his disposal, some of whom were sick and wounded.

On the night of 23rd September, the enemy army occupied the city. Opting for offense over defense, Clive brought out his troops and guns to seize the initiative. The plan spectacularly boomeranged, as Clive had not accounted for enemy snipers, who took a significant toll on his troops. With fifteen killed and nearly as many wounded, the 300 or so company troops now faced a 10,000 strong opponent. Taking them on in the open was just not an option. Clive now opted for the most logical approach: to make a stand within the fort until reinforcements would arrive.

A Desperate Stand

Outnumbered nearly 500 to 1, Clive and his men stood steady in their fort at Tiruchirapally. Fortunately for them, they had adequate provisions at least for three months and ample water available from a reservoir, thanks to the brilliant work of a local mason who managed to block the channel from which it could be drained from outside. They were also extremely fortunate in that their opponents too were content to play a waiting game, reasoning that the British would have no choice but to eventually surrender.

And so despite attacks from enemy snipers, the constant threat of a surprise attack and mounting injuries, Clive and his troops held on tenaciously for seven extraordinary weeks, as September gave way to October and October to November. With heavy guns from French Pondicherry now battering the fort and constant sniper attacks, Clive was down a measly 200 troops. While Clive steadfastly refused to surrender, he knew that his troops were on borrowed time.

The clock was rapidly ticking away.

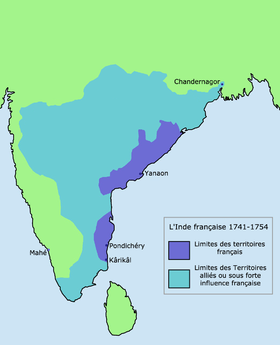

Extent of French Influence

The Miracle of Arcot

Elsewhere, events started taking a different turn. Krishnaraja Wadiyar II, the ruler of Mysore, wise to the threat posed by the Muzaffar- Chanda Sahib- French triumvirate to his independent kingdom, declared himself in favour of Mohammed Ali. The local chieftains who ruled the region from Arcot to the east coast followed suit, enabling the safe passage of English convoys from Madras to Arcot, allowing Fitzpatrick and his relieving troops free movement.

Around the same time came a far more crucial breakthrough. Even as his British allies held steadfast at Arcot, Mohammed Ali had opened a channel of communication with the Marathas. At length, the Maratha viceroy at Tanjavur, Murari Rao, agreed to dispatch a force of 6,000 soldiers to support the British. The news of the arriving reinforcements gave Clive and his forces a massive morale boost.

The news had an equally negative impact on Raza Sahib (son of Chanda Sahib), who was in charge at Arcot. Despite the 15,000 troops or so at his disposal, he knew that his forces would be no match for the mighty Marathas. In desperation, he served an ultimatum on Clive to surrender and be allowed to evacuate honourably or be annihilated. Having held fort for so long and now having the backing of the Marathas, Clive turned down the offer- a brave decisions, since his defence of the fort was in its last legs.

On 14th November 1751, Raza Sahib and his troops set out for the decisive offensive. Elephants charged at the gates to batter them down and attackers rushed forward to scale the walls. The defender’s fire put paid to the elephants which, in panic, trampled down several soldiers on their side to death. The first line of attackers were mowed down by constant firing on the breaches which they were trying to cross and the second line were blown to smithereens by British defenders, who hurled down grenades on them.

Mohammed Ali

As the battle wore on, the contrast between the well commanded and disciplined British troops and the brave but ill led troops of Raza Sahib became evident. But an equally decisive factor was the French refusal to participate in the storming of the fort, as the commander M. Goupil did not approve of the decision. As waves upon wave of troops were mowed down by the defender’s firing, it came down to who would blink first.

After an hour of indecisive fighting, Raza Sahib finally blinked, asking for a temporary ceasefire to carry of the bodies of the dead, which was granted. The ceasefire over, the pounding began again, which went on all night, but unaccompanied by charging troops. With no immediate physical threat, Clive and his troops held fort, waiting for the next round of attacks the following morning in the desperate hope that the Marathas were not too far away.

Victory!

But the expected offensive never came the following morning. As the first rays of light broke out on 15th November 1751, Clive and his troops discovered that the enemy had retreated. The previous night’s bombardment had only been a covering fire to divert attention from their flight.

Against all odds, Robert Clive and his troops had successfully held Arcot against an opponent that outnumbered them nearly 500 to 1. For the first ever time, the forces of the British East India company had defeated those of a local prince. Victory had been achieved against impossible odds.

A precedent had been set.

Siege of Arcot (23rd September to 14th November 1751)

Aftermath

- With help from its Maratha allies, the company army won decisive victories in battles against the French at Arani and Kanchipuram, effectively ensuring that the French would never become the masters of Southern India

- The final British triumph was followed by the murder of Chanda Sahib

- The losses to the British in 1752-53 marked the beginning of the end of French hegemony in the South. The East India Company would deal the coup de grace with a crushing victory in the Battle of Wandiwash (in present day Vandivasai) in 1761

- Mohammed Ali, firmly established as the nawab of Carnatic, would reign until his death in 1795

- Clive returned to England in February 1753, desiring to enter parliament. Political machinations, which blocked his passage to parliament, impelled him to return to India in July 1755.

- Dupleix died a penniless and forgotten man in November 1763

Legacy

- The defence of Arcot marks one of the most remarkable chapters in the military history of the British Raj in India. In the words of a later day biographer of Clive

There were to be few greater expeditions in the history of British arms… their feat was was achieved against staggering odds. It was an example of staggering boldness, resolution and, above all, endurance…

- The hitherto politically inactive British increasingly came to realise the dangers posed by political vagaries in India and the consequent need to get involved in local politics if only to protect their trade.

- The victories of small but professionally led armies against vastly stronger opponents brought home to the British the significance of having a professional army

- The triumph of British forces despite overwhelming odds established an aura of invincibility around the British, leading local rulers to appreciate the value of having them as allies against would be enemies

- The lessons from the earlier reverses against the French prompted the East India Company to introduce sepoy levies, which paved the way for the creation of a well trained, professional army

- The reinstatement of Mohammed Ali marked the first instance of a local ruler being installed by the East India Company. The political arrangement, which arose purely due to circumstances, served as the model on which many subsequent British conquests in India were based

- Robert Clive, hitherto a little known young writer with the East India Company, would lead the company army to far greater victories, laying the foundation for the British empire

- The French never regained their losses and consequently lost out on the race to carve out an empire in India

Sources

- George Bruce Malleson, Rulers of India: Lord Clive, Clarendon Press (1893)

- D.P. Ramachandran, Empire’s First Soldiers, Lancer Publishers (2008)

- Robert Harvey, The Life and Death of a British Emperor, Thomas Dunne Books 1st Edition (2000)